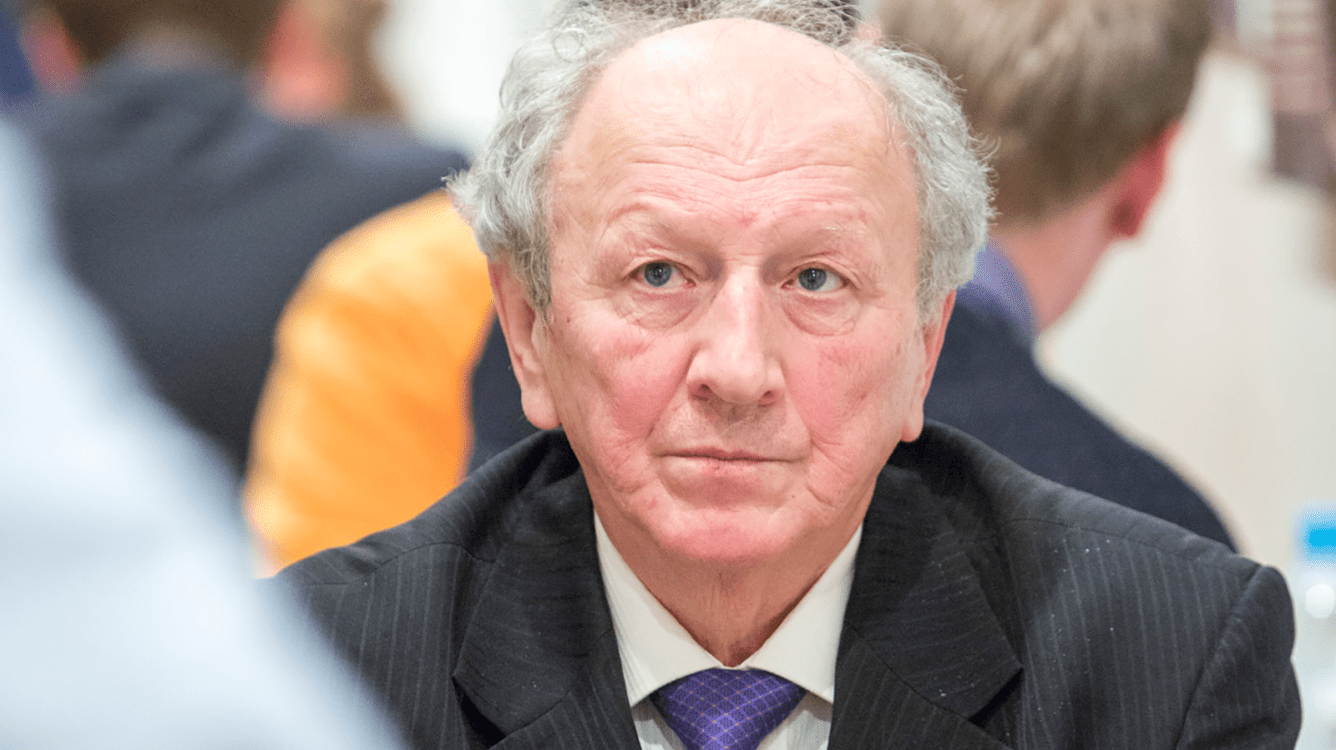

Evgeny Sveshnikov, 1950-2021

The Russian-Latvian grandmaster, former world senior champion, chess opening revolutionary, writer, trainer, and outspoken GM Evgeny Sveshnikov has passed away at the age of 71. His death came only a few months after his mother had died at the age of 95.

Evgeny Ellinovich Sveshnikov was born February 11, 1950, in Chelyabinsk, just east of the Ural mountains in Russia, then the Soviet Union. As a talented youngster, his early chess education included several lectures by the famous Soviet trainer Igor Bondarevsky. His main coach, who became a good friend, was Leonid Gratvol, himself a candidate master.

Sveshnikov's first major chess tournament was at age 17, when he played in the 35th edition of the Soviet Championship, held in December 1967 in Kharkov. For the first time, the tournament was held in the format of a 13-round Swiss with 130 players.

Just like for later GMs such as Lev Alburt, Boris Gulko, Genna Sosonko, and Rafael Vaganian, it was Sveshnikov's debut in the Soviet Championship as he scored a decent 7/13. GMs Lev Polugaevsky and Mikhail Tal shared first place.

Sveshnikov graduated in 1972 and began working as a research engineer in the Department of Internal Combustion Engines. In a ChessPro article dedicated to his 60th birthday, he was quoted about that period (translation by Chessbase):

"I worked in the laboratory for 10-12 hours a day. Under laboratory conditions, by changing the shape of the combustion chamber and increasing the degree of boost, we managed to get 100 horsepower from a single-cylinder engine of a tank. At the time the maximum was 45-50 hp. Today, tanks have 12 cylinders and 1,200 horsepower. All my life I will remember the saying of my boss, Dr. Gennady Borisovich Dragunov: 'The laws of physics are there to be circumvented by other laws of physics.' At the time I decided to become a chess professional, I had almost finished my Ph.D. thesis on the shape of the combustion chamber."

Finally able to focus on chess, Sveshnikov won the All-Union Tournaments of Young Masters in 1973 and 1976 and also the All-Union Tournament in 1975. He tied for first place with GM Sergey Makarychev in the 1983 Moscow Championship.

He came in first or shared first in a number of international tournaments, such as Plovdiv (1973), Decin (1974), Sochi (1976, 1985), Le Havre (1977), Marina Romeo (1977), Cienfuegos (1979), and Hastings (1984/1985).

In team competitions, he scored several successes. In 1976, he was part of the gold medal-winning Soviet team at the World Student Team Championship. He then won both team and individual gold at the 1977 European Team Championship, the same year when FIDE awarded his GM title.

In the 1990s, Sveshnikov moved to Riga and started representing Latvia in Chess Olympiads. He played for that country in 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010. He also played for Latvia in the European Team Championship in 2011.

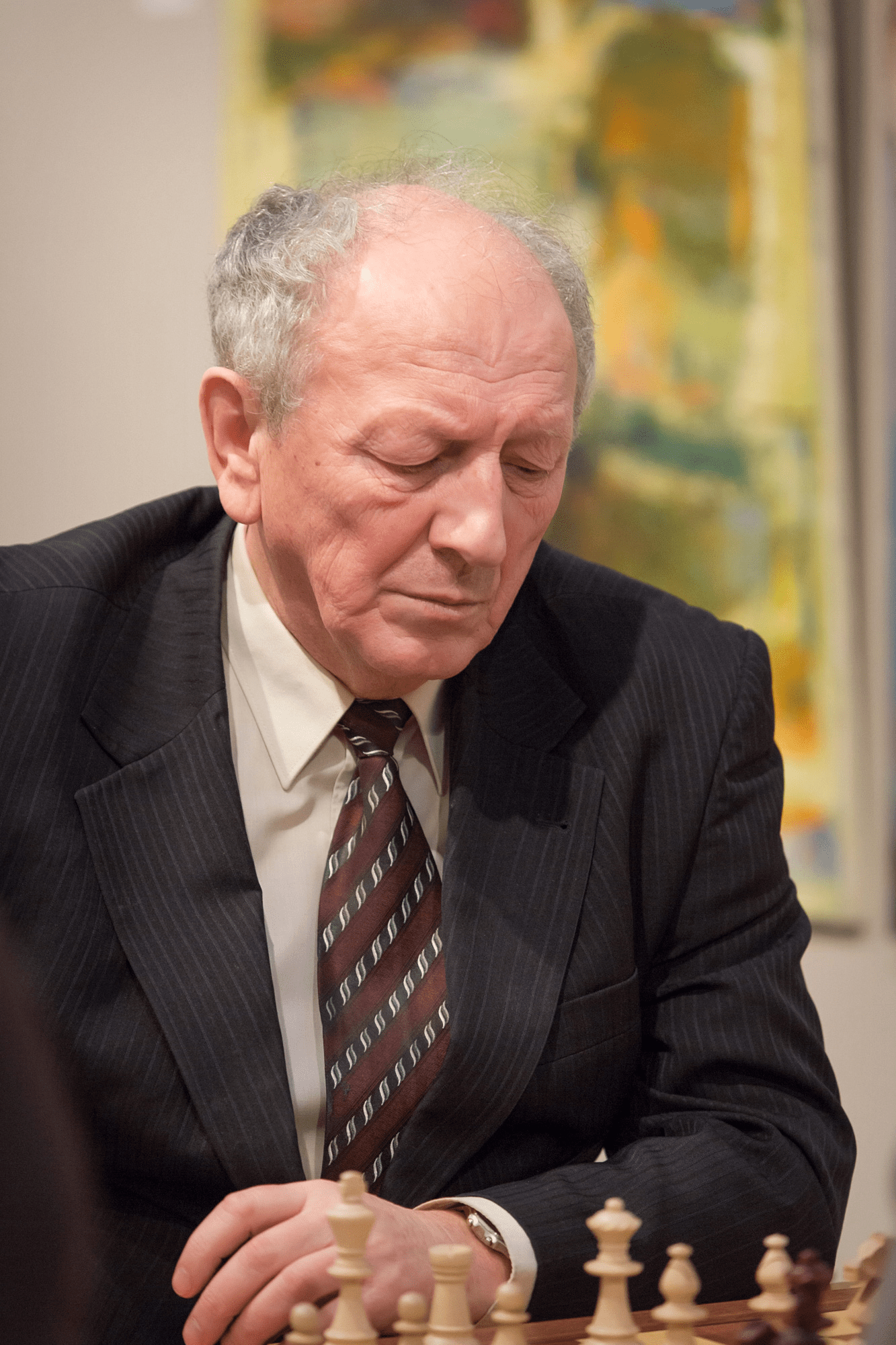

In 2016, 40 years after he had done so as a student, Sveshnikov won team gold for Russia, this time in the 65+ section of the World Senior Team Championship. A year later, he also clinched the 65+ World Senior Chess Championship.

Sveshnikov also worked as a coach. For 10 years, he was one of the leaders of the All-Russian Chess School and later he headed many regional schools, in particular in the city of Satka, close to Chelyabinsk.

During his career, Sveshnikov beat several strong grandmasters, including GM Judit Polgar, GM Viktor Korchnoi, GM Nigel Short, and GM Mark Taimanov as well as drew with (future) world champions Viswanathan Anand, Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, Vasily Smyslov, and Mikhail Tal. Here's a selection:

Sveshnikov will be remembered primarily for his contributions to opening theory—in particular the Sveshnikov variation of the Sicilian, as the moves 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 e5 have become known in the English language. Before his contributions, it was known as the Lasker-Pelikan variation and, in fact, when Sveshnikov published his own monograph in 1988, it was modestly called The Sicilian Pelikan.

Sveshnikov on the naming: "Portisch once said to me with a touch of jealousy: 'You have managed to leave your name in chess!' What he had in mind was that by the end of the 20th-century, all the major discoveries in chess had already been made."

In Russian, this particular opening variation is known as the Cheliabynsk variation because another grandmaster from the same city largely contributed to it as well: Gennadi Timoshchenko, who employed it until 1980. In his writings, Sveshnikov always mentioned that Timoshchenko played an important role in the development of the variation. (Still, in an attempt to claim at least part of the fame, Timoshchenko published a book himself on the variation in 2016.)

Once condemned as "anti-positional" for weakening the d5-square, the line was famously used as early as 1910 by the second world champion, Emanuel Lasker, in his world championship match with Carl Schlechter, who played the non-critical 6.Nb3. It soon became known that 6.Ndb5 is best, after which 6...d6 7.Bg5! is the most popular move, fighting for control of the d5-square.

At age 12 in 1962, Sveshnikov himself first saw the variation in an opening book by GM Ludek Pachman, and he felt the author's brief analysis could be improved, as demonstrated when he used it in a training match with his friend Timoshchenko in 1965 and won the first game where he tried 5...e5.

Sveshnikov had mixed but reasonably good results with the opening as his colleagues both mocked and respected him. "In the 1976 USSR Championship no one ventured to play 1.e4 against me, and I regarded this as a moral victory," Sveshnikov wrote.

When asked to send his contribution to Garry Kasparov's book Revolution in the 1970s, Sveshnikov said that he didn't think the period after 1972 was one of a revolution in openings. He considered Louis Paulsen and Aron Nimzowitsch to be the two biggest individual contributors to openings, followed by Akiba Rubinstein and theoreticians of the Soviet Chess School: Mikhail Botvinnik, Isaac Boleslavsky, Semyon Furman, Efim Geller, and Lev Polugaevsky.

"[T]he main thing I have done in chess, as a successor to Paulsen and Nimzowitsch, is to create not some individual scheme, but an entire philosophy of the opening, a system of best moves at the start of the game. This is the real 'Sveshnikov System!' In my view, it can well be considered revolutionary. To think up a rule to which there are no exceptions is far more difficult than to find exceptions to the rules."

It was in 2012 when Sveshnikov’s variation got the theoretical status of fully correct and good for equality when it was used at the highest level by GM Boris Gelfand as his main weapon against Anand's 1.e4 in their world championship match. Six years later, reigning World Champion Magnus Carlsen played the opening as well and faced 7.Nd5 instead from GM Fabiano Caruana.

In later years, Sveshnikov preferred to play the move ....e5 one move earlier, as in the Kalashnikov variation: 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5. About that switch, he wrote:

"By publishing a monograph on the 5...e5 system in 1988, I practically exhausted this variation. Since that time only some details have been developed, without introducing anything particularly new: the evaluations of the main lines have hardly changed. I described everything in such detail, that it became hard playing 5...e5 even against first category players.... I have now played more games with the 4...e5 variation than with 5...e5. And a book on this topic would be twice as thick."

After 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6, Sveshnikov himself considered 3.Bb5, the Rossolimo System, to be the best move. This followed his own set of opening principles, which he formulated as follows:

When playing White:

1) Seize the center;

2) Develop pieces;

3) Safety;

4) Attack weaknesses.

When playing Black:

1) Fight for the center;

2) Safety;

3) Develop pieces;

4) Defend and don't create weaknesses.

The Sveshnikov variation was certainly not his only contribution to opening theory. For his whole life, he has also been a devoted player of the Alapin (1.e4 c5 2.c3) and French Advance (1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.e5). On both topics, he published a book as well. He was confident about what he played, once saying: "I assure you that neither Kasparov nor Carlsen will refute my openings."

He described his general understanding of the game in the following, also very strong statement:

"Chess is an exact mathematical problem. The solution comes from two sides: the opening and the endgame. The middlegame does not exist. The middlegame is a well-studied opening. An opening should result in an endgame.... Give me five years, good assistants and modern computers, and I will trace all variations from the opening towards tablebases and 'close' chess. I feel that power."

On a personal level, Sveshnikov was known as a kind but also outspoken and controversial grandmaster. This was mostly related to his strong stance on the topic of copyright. He felt that players hold the rights over the publication of game scores and should earn royalties from any company that uses them and earns money in the process.

In a 2016 interview, Sveshnikov said about this view:

"[It] turns out that the top 20 professionals live at the expense of sponsors, and the rest? Where will they go? If in the Soviet state we had much more professionals and they all had normal salaries, therefore they provided their games. And now there is just a terrible situation because normal professionals cannot feed their families. That is, the profession has been destroyed today."

Incidentally, the concept of players receiving royalties for their games could also help in fighting short draws, as he noted in 2017:

"The only way to avoid short draws is to make them unprofitable. It can be possible if the games become a player's intellectual property. If you are the owner of a draw in 10 moves, nobody will buy it. However, fighting chess will find its customers!"

Because of his strong opinion on this topic, Sveshnikov often accepted tournament invitations on the condition that the games wouldn't be sent to commercial companies such as Chessbase or Chess Assistant. Sometimes he would refuse to hand in the score sheets and demand that his games be excluded from the live transmission.

Sveshnikov playing street chess in Riga in 2018.

Another controversy occurred in 2011, when Sveshnikov sued the Russian Chess Federation for not allowing him to play in championships on Russian soil because he was representing Latvia. He considered this discriminatory and therefore illegal.

He lost the case and appealed in every jurisdiction, even in Europe, but lost everywhere. However, a few months after he ended his legal battle, the federation allowed him in their tournaments after all.

Later, he switched federations back to Russia. His son Vladimir, who is an international master, still represents Latvia.

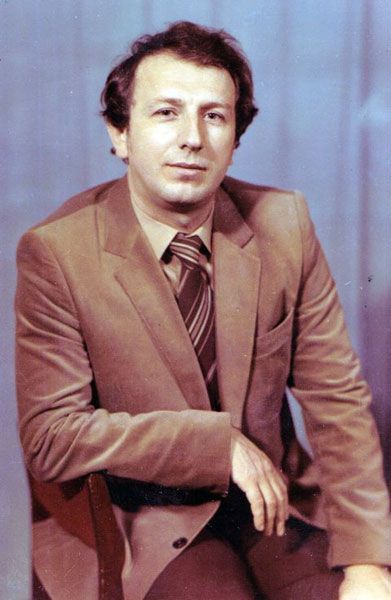

On January 10, 1984 Sveshnikov was diagnosed with third-stage cancer. Fearing for his life, he had a photographic portrait made for his children, but he survived.

During the pandemic, Sveshnikov carried a document with him that said he could not get vaccinated due to health issues. He did not like to wear face masks and felt that Covid-19 was not very dangerous, even when his son was tested positive and briefly hospitalized. According to a Russian journalist close to Sveshnikov, he contracted the virus as well and was also briefly hospitalized. He was discharged but died from complications. “I think Covid had something to do with it, but it was not the main reason,” his son Vladimir clarified to Chess.com.

Yury Solomatin contributed to this obituary.

Evgeny Sveshnikov (1950-2021) passed away. The Chess Federation of Russia expresses sincere condolences to the family and friends of the well-known grandmaster and theoretician.

— Chess Federation of Russia (@ruchess_eng) August 18, 2021

Photo: Vladimir Barsky #CFR pic.twitter.com/DtrNx9gjfW

Evgeny Sveshnikov passed away. A strong grandmaster who foresaw many interesting trends and greatly enriched chess theory. RIP.

— Yan Nepomniachtchi (@lachesisq) August 18, 2021

Грустные новости пришли из Москвы сегодня. Ушёл из жизни Евгений Эллинович Свешников🙏🏻. В далеком 1999 именно Свешников показал мне план с h4 в одном из вариантов Алапина, который я применяю и сегодня. А в 2003 был моим секундантом во время матча в Бриссаго. Светлая память! pic.twitter.com/lBoHdbUWSJ

— Alexandra Kosteniuk (@chessqueen) August 18, 2021

Very sad to hear about the passing away of GM. Evgeny Sveshnikov . In my career I have spent a lot of time studying the “Sveshnikov”. I always admired his love for the game and his willingness to share it. I treasure the memory of my games with him. R. i.P

— Viswanathan Anand (@vishy64theking) August 19, 2021

Oh no, I hear that Evgeny has passed away. He was a titan, and a very lovely guy. https://t.co/16lgpwdb3M

— Jonathan Tisdall (@GMjtis) August 18, 2021

Sad news, Sveshnikov passed away today. I met him for the first time in Moscow Olympiad 1994, he came to my room together with Alexey Kuzmin to congratulate me on my win over GM Milos. That was special moment for me. RIP

— Mohamed Al-Mudahka (@almodiahki) August 18, 2021

Sad news, Sveshnikov was a influential thinker, with one of the major chess-openings bearing his name.

— Peter Heine Nielsen (@PHChess) August 18, 2021

I saw him play in his hometown Chelyabinsk in 1991, and his board was surrounded by spectators.

RIP. https://t.co/oY2GlOLKoO

RIP Evgeny Sveshnikov (1950-2021). I met him 2012 during the World Championship 2012 in Moscow. He visited the 5th game, in which "his" opening was played. #sveshnikov pic.twitter.com/z1U52nT6zd

— Let's talk about chess (@ChessClassic) August 18, 2021

Correction: an earlier version of this article erroneously stated that the 35th edition of the Soviet Championship was held in Tbilisi, Georgia. It was in Kharkov.